-40%

Civil War CDV Union General Daniel Sickles Lost Leg at Gettysburg

$ 66

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

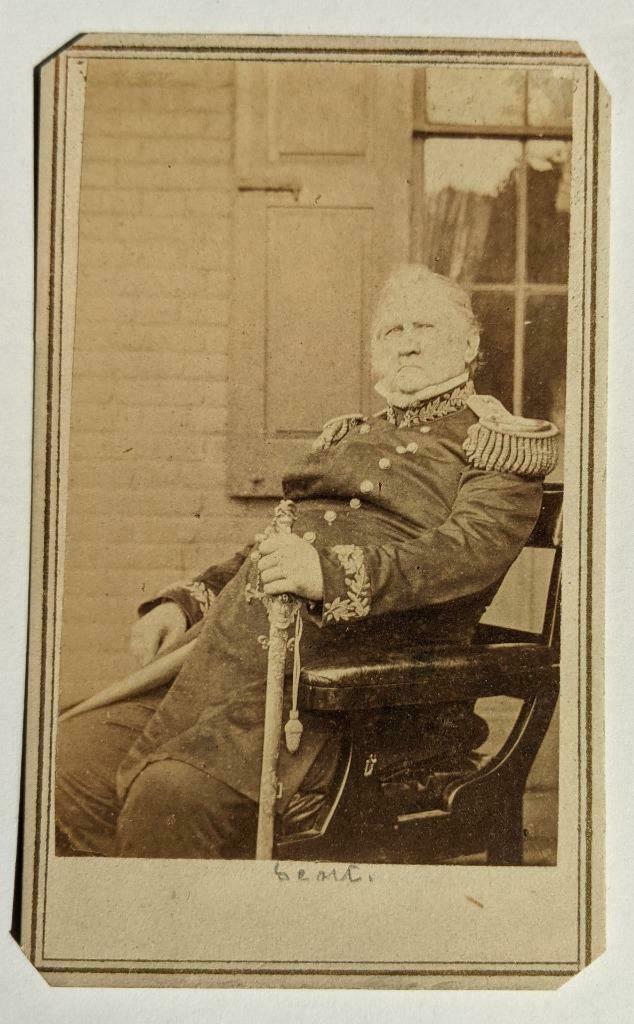

Condition as seen.Daniel Edgar Sickles (October 20, 1819 – May 3, 1914) was an American politician, soldier, and diplomat.

Born to a wealthy family in New York City, Sickles was involved in a number of scandals, most notably the 1859 homicide of his wife's lover, U.S. Attorney Philip Barton Key II, whom Sickles gunned down in broad daylight in Lafayette Square, across the street from the White House.[2] He was acquitted after using temporary insanity as a legal defense for the first time in United States history.

Upon the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, Sickles became one of the war's most prominent political generals, recruiting the New York regiments that became known as the Excelsior Brigade in the Army of the Potomac. Despite his lack of military experience, he served as a brigade, division, and corps commander in some of the early Eastern campaigns. His military career ended at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, after he moved his III Corps without orders to an untenable position, where they were decimated but slowed General James Longstreet's flanking maneuver. Sickles himself was wounded by cannon fire at Gettysburg and had to have his leg amputated. He was eventually awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions.[3]

Sickles devoted considerable effort to trying to gain credit for helping achieve the Union victory at Gettysburg, writing articles and testifying before Congress in a manner that denigrated the intentions and actions of his superior officer, Maj. Gen. George Meade. After the war, Sickles was appointed as a commander for military districts in the South during Reconstruction. He also served as U.S. Minister to Spain under President Ulysses S. Grant. Later he was re-elected to Congress, where he helped pass legislation to preserve the Gettysburg Battlefield.[4]

Contents

1

Early life and politics

1.1

Homicide of Key

1.2

Trial

2

Civil War

2.1

Gettysburg

3

Postbellum career

4

Death

5

In popular media

6

Medal of Honor citation

7

Images

8

See also

9

Notes

10

References

11

Further reading

12

External links

Early life and politics

In 1819, Sickles was born in New York City to Susan Marsh Sickles and George Garrett Sickles, a patent lawyer and politician.[5] (His year of birth is sometimes given as 1825, and Sickles was known to have claimed as such. Historians speculate that Sickles chose to appear younger when he married a woman half his age.) He learned the printer's trade and studied at the University of the City of New York (now New York University).[6] He studied law in the office of Benjamin Butler, was admitted to the bar in 1846, and was elected as a member of the New York State Assembly (New York Co.) in 1847.[5]

On September 27, 1852, Sickles married Teresa Bagioli against the wishes of both families—he was 32, she about 15 or 16.[7] She was reported as sophisticated for her age, speaking five languages.

In 1853 Sickles became corporation counsel of New York City, but resigned soon afterward when appointed as secretary of the U.S. legation in London, under James Buchanan,[6] by appointment of President Franklin Pierce. In 1855 he returned to the United States, and in 1856 he was elected as a member of the New York State Senate in the 3rd D.. He was re-elected to the seat in 1857. In 1856 he was also elected as a Democrat to the 35th U. S. Congress, and held office from March 4, 1857, to March 3, 1861, a total of two terms.[citation needed]

Homicide of Key

Sickles shoots Key in 1859

Sickles was censured by the New York State Assembly for escorting a known prostitute, Fanny White, into its chambers. He also reportedly took her to England, while leaving his pregnant wife at home. He presented White to Queen Victoria, using as her alias the surname of a New York political opponent.[5]

On February 27, 1859, in Lafayette Square, across the street from the White House, Sickles shot and killed Philip Barton Key II, the district attorney of the District of Columbia[8] and the son of Francis Scott Key. Sickles had discovered that Philip Key was having an affair with his young wife.[2][9]

Trial

"You are here to fix the price of the marriage bed!", roared Associate Defense Attorney John Graham, in a speech so packed with quotations from Othello, Judaic history and Roman law that it lasted two days and later appeared as a book.

Time magazine article, "Yankee King of Spain", June 18, 1945[10]

Sickles surrendered at Attorney General Jeremiah Black's house, a few blocks away on Franklin Square, and confessed to the murder. After a visit to his home, accompanied by a constable, Sickles was taken to jail. He received numerous perquisites, including being allowed to retain his personal weapon, and receive numerous visitors. So many visitors came that he was granted the use of the head jailer's apartment to receive them.[11] They included many congressmen, senators, and other leading members of Washington society. President James Buchanan sent Sickles a personal note.[citation needed]

The trial of Sickles. Engraving from Harper's.

Harper's Magazine reported that the visits of his wife's mother and her clergyman were painful for Sickles. Both told him that Teresa was distracted with grief, shame, and sorrow, and that the loss of her wedding ring (which Sickles had taken on visiting his home) was more than Teresa could bear.[citation needed]

Sickles was charged with murder. He secured several leading politicians as defense attorneys, among them Edwin M. Stanton, later to become Secretary of War, and Chief Counsel James T. Brady who, like Sickles, was associated with Tammany Hall.[citation needed] Sickles pleaded temporary insanity—the first use of this defense in the United States.[12] Before the jury, Stanton argued that Sickles had been driven insane by his wife's infidelity, and thus was out of his mind when he shot Key. The papers soon trumpeted that Sickles was a hero for "saving all the ladies of Washington from this rogue named Key".[13]

Sickles had obtained a graphic confession from Teresa; it was ruled inadmissible in court, but, was leaked by him to the press and printed in the newspapers in full. The defense strategy ensured that the trial was the main topic of conversations in Washington for weeks, and the extensive coverage of national papers was sympathetic to Sickles.[14] In the courtroom, the strategy brought drama, controversy, and, ultimately, an acquittal for Sickles.[15]

Sickles publicly forgave Teresa, and "withdrew" briefly from public life, although he did not resign from Congress. The public was apparently more outraged by Sickles's forgiveness and reconciliation with his wife than by the murder and his unorthodox acquittal.[16]

Civil War

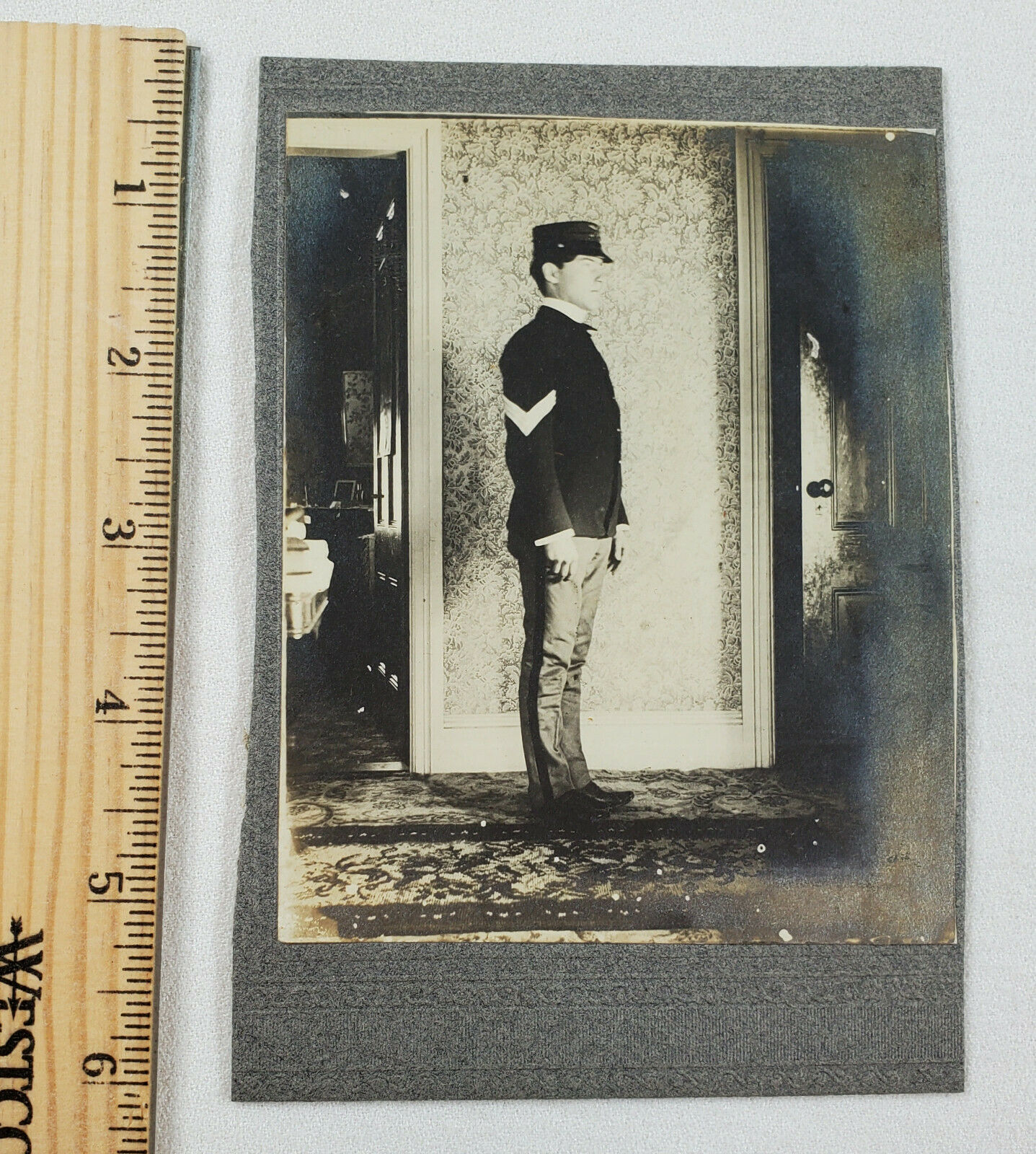

Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, [ca. 1859–1870]. Carte de Visite Collection, Boston Public Library

In the 1850s, Sickles had received a commission in the 12th Regiment of the New York Militia, and had attained the rank of major.[17] (He insisted on wearing his militia uniform for ceremonial occasions while serving in London, and caused a minor diplomatic scandal by snubbing Queen Victoria at an Independence Day celebration.[18])

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Sickles worked to repair his public image by raising volunteer units in New York for the Union Army. Because of his previous military experience and political connections, he was appointed colonel of one (the 70th New York Infantry) of the four regiments he organized.[19] He was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers in September 1861, where he was notorious before beginning any fighting.

According to author Garry Boulard's Daniel Sickles: A Life, Sickles not only refused to return runaway slaves who escaped to his Union camp in Northern Virginia, he put many of them on the federal payroll as servants, while also training male slaves to be soldiers. It was a policy that won for him the approval of the influential Committee on the Conduct of the War.

In March 1862, he was forced to relinquish his command when the U.S. Congress refused to confirm his commission. He lobbied his Washington political contacts and reclaimed both his rank and his command on May 24, 1862, in time to rejoin the Army in the Peninsula Campaign.[5] Because of this interruption, Sickles missed his brigade's significant actions at the Battle of Williamsburg. Despite his lack of previous combat experience, he did a competent job commanding the "Excelsior Brigade" of the Army of the Potomac in the Battle of Seven Pines and the Seven Days Battles. He was absent for the Second Battle of Bull Run,[9] having used his political influences to obtain leave to go to New York City to recruit new troops. He also missed the Battle of Antietam because the III Corps, to which he was assigned as a division commander, was stationed on the lower Potomac, protecting the capital.[citation needed]

Sickles was a close ally of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, his original division commander, who eventually commanded the Army of the Potomac. Both men had notorious reputations as political climbers and as hard-drinking ladies' men. "Accounts at the time compared their army headquarters to a rowdy bar and bordello."

Sickles' division was in reserve at the Battle of Fredericksburg. On January 16, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln nominated Sickles for promotion to the grade of major general to rank from November 29, 1862.[20] Although the U.S. Senate did not confirm the promotion until March 9, 1863, and the President did not formally appoint Sickles until March 11, 1863,[20] Hooker, now commanding the Army of the Potomac, gave Sickles command of the III Corps in February 1863.

This decision was controversial as Sickles became the only corps commander without a West Point military education. His energy and ability were conspicuous in the Battle of Chancellorsville. He aggressively recommended pursuing troops he saw in his sector on May 2, 1863. Sickles thought the Confederates were retreating, but these turned out to be elements of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's corps, stealthily marching around the Union flank. He also vigorously opposed Hooker's orders moving him off good defensive terrain in Hazel Grove. In both of these cases, it is easy to imagine the disastrous battle turning out very differently for the Union if Hooker had heeded his advice.

— Charles Hanna, [21]

Gettysburg

Map of battle, July 2. Sickles' movement of III Corps can be seen in the southwestern quadrant.

Confederate

Union

The Battle of Gettysburg was the occasion of the most famous incident and the effective end of Sickles' military career. On July 2, 1863, Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade ordered Sickles' corps to take up defensive positions on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge, anchored in the north to the II Corps and to the south, the hill known as Little Round Top. Sickles was unhappy to see the "Peach Orchard," a slightly higher terrain feature, to his front.[22] Concerned over his position and uncertain of Meade's exact intentions, a little after 2 p.m. he began to march his corps out to the Peach Orchard, almost a mile in front of Cemetery Ridge.[23] This had two effects: it greatly diluted the concentrated defensive posture of his corps by stretching it too thin, and it created a salient that could be bombarded and attacked from multiple sides. Soon thereafter (3 p.m.), Meade called a meeting of his corps commanders.[22] An aide to Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren soon reported the situation.[22] Sickles arrived just after the meeting had ended. Meade and Warren rode with Sickles back to his position, where Meade explained Sickles' error.[24] Meade refused Sickles' offer to withdraw because he realized it was too late[25] and the Confederates would soon attack, putting a retreating force in even greater peril.[22]

The Confederates attacked at about the time Meade spoke with Sickles and then returned to his headquarters.[24] The Confederate assault by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's corps, primarily by the division of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, smashed the III Corps and rendered it useless for further combat. Gettysburg campaign historian Edwin B. Coddington assigns "much of the blame for the near disaster" in the center of the Union line to Sickles.[26] Stephen W. Sears wrote that "Dan Sickles, in not obeying Meade's explicit orders, risked both his Third Corps and the army's defensive plan on July 2.[27] However, Sickles' maneuver has recently been credited by John Keegan with blunting the whole Confederate offensive that was intended to cause the collapse of the Union line.[28] Similarly, James M. McPherson wrote that "Sickles's unwise move may have unwittingly foiled Lee's hopes."[25]

During the height of the Confederate attack, Sickles was wounded by a cannonball that mangled his right leg. He was carried by a detail of soldiers to the shade of the Trostle farmhouse, where a saddle strap was applied as a tourniquet. He ordered his aide, Major Harry Tremain, "Tell General Birney he must take command." As Sickles was carried by stretcher to the III Corps hospital on the Taneytown Road, he attempted to raise his soldiers' spirits by grinning and puffing on a cigar along the way.[29] His leg was amputated that afternoon. He insisted on being transported to Washington, D.C., which he reached on July 4, 1863. He brought some of the first news of the great Union victory, and started a public relations campaign to defend his behavior in the conflict. On the afternoon of July 5, President Lincoln and his son, Tad, visited General Sickles, as he was recovering in Washington.[30]

Sickles's leg, along with a cannonball similar to the one that shattered it, on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine

Sickles had recent knowledge of a new directive from the Army Surgeon General to collect and forward "specimens of morbid anatomy ... together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed" to the newly founded Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C. He preserved the bones from his leg and donated them to the museum in a small coffin-shaped box, along with a visiting card marked, "With the compliments of Major General D.E.S." For several years thereafter, he reportedly visited the limb on the anniversary of the amputation. The museum, now known as the National Museum of Health and Medicine, still displays this artifact. (Other Civil War-era specimens of note on display include the hip of General Henry Barnum.)

Sickles ran a vicious campaign against General Meade's character after Gettysburg. Sickles felt that Meade had wronged him and that he deserved credit for winning the battle. In anonymous newspaper articles and in testimony before a congressional committee, Sickles falsely maintained that Meade had secretly planned to retreat from Gettysburg on the first day.[31] He also claimed to have occupied Little Round Top on July 2.[32] While his movement away from Cemetery Ridge may have violated orders, Sickles always asserted that it was the correct move because it disrupted the Confederate attack, redirecting its thrust, and effectively shielding the Union's real objectives, Cemetery Ridge and Cemetery Hill.[33] Sickles's redeployment took Confederate commanders by surprise, and historians have argued about its ramifications ever since.

Sickles eventually received the Medal of Honor for his actions, although it took him 34 years to get it. The official citation accompanying his medal recorded that Sickles "displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field, vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded."[34]

Postbellum career

Despite his one-legged disability, Sickles remained in the army until the end of the war and was disgusted that Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant would not allow him to return to a combat command. In 1867, he received appointments as brevet brigadier general and major general in the regular army for his services at Fredericksburg and Gettysburg, respectively.[6]

Soon after the close of the Civil War, in 1865, he was sent on a confidential mission to Colombia (the "special mission to the South American Republics") to secure its compliance with a treaty agreement of 1846 permitting the United States to convey troops across the Isthmus of Panama.[6] From 1865 to 1867, he commanded the Department of South Carolina, the Department of the Carolinas, the Department of the South, and the Second Military District. Sickles pursued reconstruction on a basis of fair treatment for African-Americans and respect for the rights of employees. He halted foreclosures on property. He also made the wages of farm laborers the first lien on crops. He outlawed discrimination against African-Americans and banned the production of whisky.[35]

In 1866, he was appointed colonel of the 42nd U.S. Infantry (Veteran Reserve Corps), and in 1869 he was retired with the rank of major general.[6]

Sickles served as U.S. Minister to Spain from 1869 to 1874, after the Senate failed to confirm Henry Shelton Sanford to the post, and took part in the negotiations growing out of the Virginius Affair. His inaccurate and emotional messages to Washington promoted war, until he was overruled by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and the war scare died out.

In his Daniel Sickles: A Life Garry Boulard points out that Sickles was disadvantaged throughout the Virginius controversy, trying to negotiate with a Spanish leadership that was frequently disorganized and chaotic, while the substantial talks were taking place in Washington between Fish and Spanish Minister Don Jose Polo de Barnabe. Even so, when Sickles subsequently decided to turn in his resignation, Fish, who was not displeased with Sickles' service, wired the General: "You are recalled on your own request."[36]

Generals Joseph Carr, Sickles, and Charles Graham in 1886, near the Trostle Barn where Sickles was wounded at Gettysburg

Sickles maintained his reputation as a ladies' man in the Spanish royal court and was rumored to have had an affair with the deposed Queen Isabella II. Following the death of Teresa in 1867, in 1871 he married Carmina Creagh, the daughter of Chevalier de Creagh of Madrid, a Spanish Councillor of State. They had two children.[37]

Starting in the 1880s and continuing until nearly the end of his life, Sickles frequently attended and spoke at Gettysburg reunions as the former commander of the III Corps in the victorious Army of the Potomac, popular with many of the veterans who had served under his command.[38] He also struck up a friendship with former opponent James Longstreet, one who was also seeking to defend himself from attacks (many politically motivated in Longstreet’s case) over his war performance.[39] Sickles’ popularity with veterans was not universal, however, because of his inflated claims that he was the ultimate father of the Union victory and his repeated attacks against George Meade, even after Meade’s death in 1872, with falsehoods about Meade wanting to retreat from Gettysburg.[40]

Excelsior Brigade monument at Gettysburg

The New York Monuments Commission was formed in 1886 and Sickles was appointed honorary chairman. He served the commission zealously for most of the rest of his life in securing appropriations for monuments to New York regiments, batteries, and commanders and having them placed correctly on the Gettysburg battlefield.[41] He was forced out of the Commission in 1912, however, when ,000 was found to have been embezzled.[42] Sickles was appointed as chairman of the New York State Civil Service Commission from 1888 to 1889, and Sheriff of New York County in 1890. In 1891, he was elected to the board of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association.[43] In 1892, he was elected again as a Democratic representative in the 53rd Congress, serving from 1893 to 1895.[44]

As a congressman, Sickles had an important part in efforts to preserve the Gettysburg Battlefield, sponsoring legislation to form the Gettysburg National Military Park, buy up private lands, and erect monuments. He procured the original fencing used on East Cemetery Hill to mark the park's borders. This fencing came directly from Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C.[45] In fact, the park's borders were defined from its establishment until 1974 by a map prepared by Dan Sickles.[46]

Of the principal senior generals who fought at Gettysburg, virtually all, with the conspicuous exception of Sickles, have been memorialized with statues. When asked why there was no memorial to him, Sickles supposedly said, "The entire battlefield is a memorial to Dan Sickles." The monument to the New York Excelsior Brigade was originally commissioned to include a bust of Sickles, but it includes a figure of an eagle instead.[47]

Death

Sickles' funeral

Sickles lived out the remainder of his life in New York City, dying on May 3, 1914 at the age of 94. His funeral was held at St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan on May 8, 1914. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[48][34][49][50]

In popular media

American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles is a 2002 biography by the novelist Thomas Keneally.

Sickles is featured in the alternate history novels, Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War (2003) and Grant Comes East (2004), the first two books of the Civil War trilogy by Newt Gingrich and William R. Forstchen.

In Stephen L. Carter's 2012 alternate history novel, The Impeachment of Abraham Lincoln, Sickles is featured as one of the defense counsel in Lincoln's trial before the United States Senate.

A recreation of Sickles’ leg is briefly featured on display in the 2012 film “Lincoln.”

The account of Sickles' discovery of his wife's affair with Philip Barton Key, his murder of Key, and the subsequent trial are the subject of Chris DeRose's nonfiction book, Star Spangled Scandal: Sex, Murder, and the Trial that Changed America (2019).

The assassination of Philip Barton Key and the mystery of who wrote the Sickles' letter were covered in a 2019 episode of the Unresolved podcast.

The Battle of Gettysburg Podcast regularly features a "Sickles Report." It dedicated episodes 3 and 4 of its second season to Sickles' murder of Key and its subsequent links to the Battle of Gettysburg; the episode was recorded inside the house at the Sherfy Farm at Gettysburg National Military Park. The podcast also dedicated episodes 4 and 5 of its first season to the battle for the Peach Orchard, including Sickles' motivations for taking the position on July 2.[51] Jim Hessler, who wrote the 2009 book Sickles at Gettysburg and co-authored the 2019 book Gettysburg's Peach Orchard with Britt Isenberg, co-hosts the podcast with Eric Lindblade.

Medal of Honor citation